Some speculate that she wants to prove her "red-blooded American patriotism" to become "beloved by the tennis world" (31). On September 11, 2011, Serena goes after the Grand Slam cup once again. Serena explodes at the line judge, having been thrown against a sharp white background. The announcers denounce the call, and numerous replays cannot indicate the moment of foul. The body has a memory of its own when Serena is back on the court, she will be watched by a line judge who calls her out for stepping on the line during a critical serve. The next year, the tournaments would install line-calling technology to challenge umpire callings via replay. The narrator suggests that it must have been Serena's black body that was "getting in the way of Alves's sight line" (29). The most notorious oppositional force in her career has been the umpire Mariana Alves, who made five bad calls against Serena in one match back in 2004. Zora Neale Hurston once said, "I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background" the narrator uses this statement to frame the situation of Serena being a black player in an overwhelmingly white sport. At this point, Rankine places the reader in the point of view of a posh tennis-watcher: "Oh my God, she's gone crazy, you say to no one" (27).

One example of this is at the 2009 Women's US Open final when Serena Williams allowed her rage to be seen. However, it can also be seen not as anger, but rather as insanity.

This type of anger provides presence where erasure occurs.

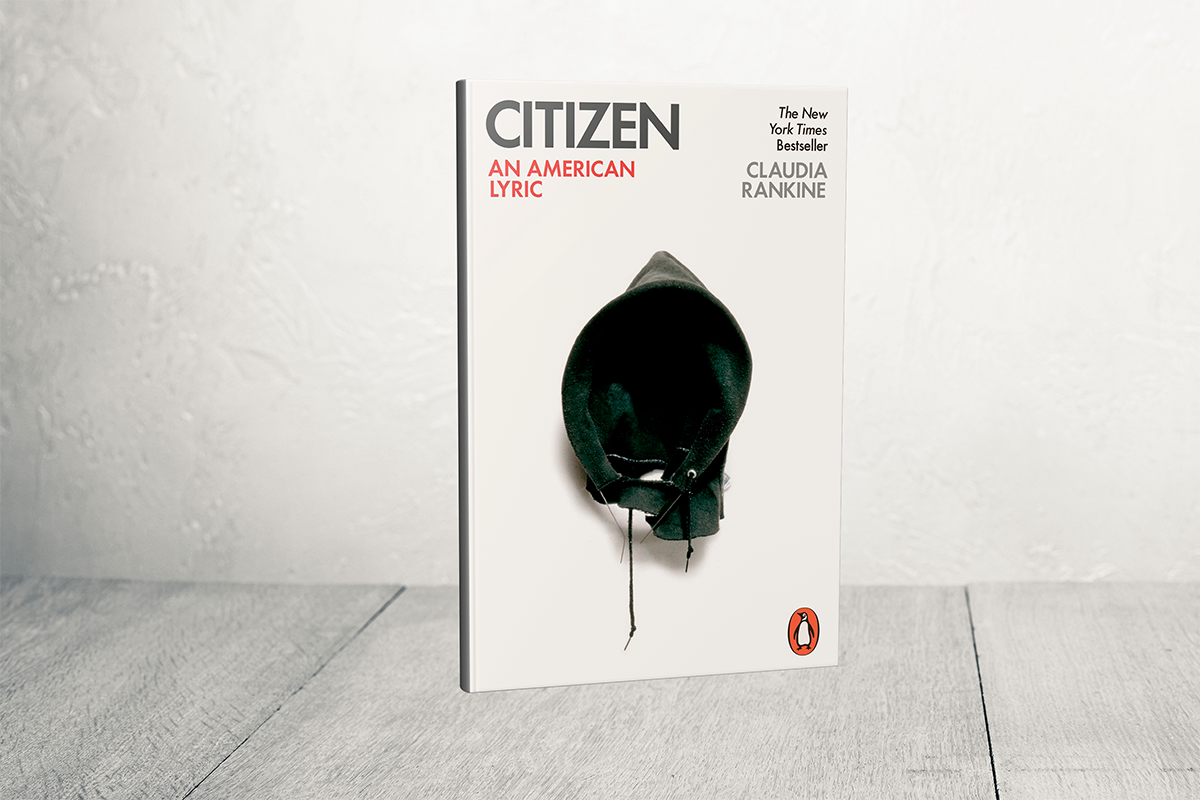

Therefore any real anger, such as that experienced in Section I, cannot produce sellable art, but only loneliness. The narrator explains that this is meant to uncover the expectations of commodified anger in black artists. On his YouTube channel, this YouTube artist encourages black artists to watch the Rodney King video while working to create an angrier exterior. A picture of Hennessy Youngman (aka Jayson Musson) accompanies the first page of Section II.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)